Bacillus Subtilis as a Model Organism for Cellular Research: Fundamental Discoveries in Sporulation, Stress Response, and Cellular Differentiation

- Stanislav M.

- Jan 24

- 12 min read

Updated: 5 days ago

Why Bacillus Subtilis Changed Biology

In 1997, Bacillus subtilis became the first Gram-positive bacterium to have its complete genome sequenced. This watershed moment opened a door to understanding how billions of Gram-positive bacteria—from beneficial soil organisms to serious human pathogens—organize their genetic information and coordinate biological processes. Yet the genome sequence alone does not explain why B. subtilis has become arguably the most important microbial model organism after E. coli. The answer lies not in any single feature but in an extraordinary combination: genetic tractability rivaled only by E. coli, an unparalleled ability to undergo cellular differentiation through sporulation, a sophisticated stress response system, and a 180-year research legacy producing one of the most complete functional annotations of any living organism.

For cellular biologists, developmental biologists, and microbiologists, B. subtilis answers fundamental questions that cannot be asked in other model systems: How does a single genome create two distinct cell types? How does a cell remember and respond to its past stress history? What makes a spore so resistant that it can survive boiling water, decades of dormancy, and extreme environmental conditions? This blog explores why B. subtilis has become the premier cellular research model, focusing on the two processes that define its research value: sporulation—the elegant demonstration of bacterial development—and the general stress response—a sophisticated system for environmental sensing and adaptation.

Why Bacillus subtilis: The Case for a Model Organism

Genetic Tractability: A Research Powerhouse

Unlike most bacteria, Bacillus subtilis is naturally transformable—it spontaneously takes up naked DNA from the environment, integrates it into its chromosome, and produces heritable mutations. This capability, discovered decades ago, has made B. subtilis the platform of choice for bacterial genetics.

Advantages of Natural Transformation:

No need for expensive electroporation equipment or chemical methods

Efficient DNA uptake across entire population

Easy creation of strains with specific mutations

Straightforward gene replacement and deletion

Compatible with CRISPR/Cas9 and modern molecular tools

Beyond transformation, B. subtilis possesses an exceptionally powerful genetic toolbox—decades of innovation have produced systems for:

Cell-type specific gene expression (sporulation σ factors enable tissue-like specificity)

Inducible gene expression (aTc/xylA systems for tight temporal control)

Protein tagging and localization (GFP fusion proteins; fluorescent microscopy)

Conditional protein depletion (STRP system enables fast degradation of proteins in specific cell types)

Gene essentiality screening (transposon mutagenesis identifies essential genes)

This genetic sophistication—matching or exceeding E. coli in some respects—enables experiments impossible in other bacterial systems.

Get full information about :Benefits, Environmental Role, Industrial Applications, and Intestinal Health.

Rapid Growth & Practical Feasibility

B. subtilis grows rapidly (doubling time ~20 minutes in rich media), allowing:

High-throughput experiments

Large-scale culture for protein/RNA extraction

Quick serial transfers maintaining genetic stability

Cost-effective research (minimal media supports growth)

Easy cultivation in standard laboratory incubators

Contrast this with pathogens like Mycobacterium tuberculosis (doubling time 15-20 hours) or fastidious organisms requiring specialized media—B. subtilis enables experimental feasibility across diverse research contexts.

The Unique Advantage: Endospore Formation

While hundreds of bacteria have been studied, B. subtilis is the model organism for sporulation—the process of forming highly resistant, dormant spores. E. coli cannot form spores. Most clinical pathogens cannot be easily studied for sporulation. Pathogenic Bacillus species (B. anthracis, B. cereus) are difficult to work with, requiring biosafety containment.

B. subtilis sporulation represents the simplest cellular differentiation process in prokaryotes. Unlike eukaryotic development with thousands of cell types and months of differentiation, B. subtilis creates two distinct cell types in 8 hours from a single genome. This simplicity makes B. subtilis ideal for understanding developmental principles applicable across biology.

Sporulation: Bacterial Development as a Research Model

The Challenge: Creating Two Cell Types from One Genome

When nutrients become limiting (particularly nitrogen and carbon sources), individual B. subtilis cells face a critical choice: attempt to survive as vegetative cells or enter a developmental program creating dormant spores. This developmental decision sets in motion a precisely orchestrated 8-hour program transforming a single exponentially growing cell into a metabolically inert, physically distinct spore.

The Central Challenge: How does the same genome—without gene duplication or DNA modification—produce two functionally distinct cell compartments?

The Answer: Through developmental gene regulation of astonishing sophistication.

The Seven Stages of Sporulation

Stage 0-I: Initiation (0-1 hours)

The sporulation decision begins with nutrient sensing. When cells detect starvation, sensor kinase proteins activate. These kinases phosphorylate a series of proteins in a phosphorelay—essentially a molecular bucket brigade passing a phosphate group:

Sensor kinase → SpoOF (phosphotransferase) → SpoOB (phosphotransferase) → Spo0A (master regulator)

Spo0A~P (phosphorylated Spo0A) accumulates to critical threshold levels. This protein is the master developmental switch—genes controlled by Spo0A~P include:

Early sporulation genes (spo genes)

Sigma factor genes (sigE, sigF, sigG, sigK for cell-specific gene expression)

DNA replication inhibition genes

Quorum Sensing Element: Cell density influences sporulation probability. Autoinducer molecules accumulate at high cell density, promoting Spo0A~P accumulation. This ensures sporulation occurs only when populations are sufficiently dense—advantageous for spore survival and germination.

Research Insight: The phosphorelay exemplifies how bacteria use two-component signaling systems to sense environmental conditions and convert those signals into gene expression changes.

Stage II: Asymmetric Septation (1-2 hours)

This stage represents the most dramatic morphological change in spore formation. Rather than dividing midway down the cell axis (as vegetative cells do), the septum forms near the cell pole, creating an asymmetric division:

Forespore: The smaller compartment (~25% of cell volume), containing one chromosomal copy

Mother cell: The larger compartment (~75% of cell volume), containing one chromosomal copy

The Remarkable Fact: The cell creates specific proteins that localize to the pole, organizing the asymmetric septum. Proteins like DivIB, FtsZ (the division-orchestrating protein), and others concentrate at the pole, directing septum formation to this asymmetric location rather than the cell midpoint.

Research Questions Answered:

How do cells create asymmetry? (Polar localization of proteins)

What drives asymmetric division? (Specific signaling molecules)

How does asymmetric division generate cell fate differences? (Different environment → different gene expression)

Stage III-IV: Engulfment (2-4 hours)

Following asymmetric septation, the mother cell undergoes an extraordinary process: the mother cell membrane extends around the forespore, engulfing it.

Engulfment Mechanism:

Pores form in the septum (transient channels)

Mother cell wall remodels

Mother cell membranes extend around forespore

A double-membrane envelops the forespore (similar to eukaryotic endocytosis but in bacteria)

The Remarkable Discovery: During engulfment, forespore and mother cell remain connected by proteinaceous channels—likely protein structures through which metabolites and possibly larger molecules can pass. These channels are transient; they eventually seal as development progresses.

Key Proteins: SpoIID, SpoIIM, SpoIIP (channel components; identified through mutational analysis)

Research Significance: Demonstrates intercellular communication across membranes in bacteria—fundamental to understanding how multicellular processes might have evolved.

Stage V-VI: Spore Maturation & Coat Assembly (4-7 hours)

The developing spore undergoes dramatic biochemical changes:

Peptidoglycan Remodeling: The cell wall surrounding the forespore is extensively modified, creating a specialized structure capable of resisting extreme conditions.

Dipicolinic Acid (Ca²⁺-DPA) Accumulation: The forespore accumulates massive quantities of dipicolinic acid complexed with calcium. This compound:

Comprises ~5-15% of spore dry weight

Densifies the spore core

Contributes to heat resistance

Provides calcium for spore activation (germination)

Small Acid-Soluble Proteins (SASPs): The forespore produces proteins that bind DNA, protecting chromosomal DNA from:

UV radiation (100x more resistant than vegetative DNA)

Chemical damage

Oxidative stress

Heat

Spore Coat Assembly: >20 proteins assemble in ordered layers forming the external spore coat—a complex polymer providing additional protection.

Mother Cell Lysis: As spore maturation completes, the mother cell lyses (undergoes programmed cell death), releasing the mature spore.

Stage VII: Germination & Return to Growth

The mature spore is metabolically inert—barely alive. Yet when favorable conditions return (nutrients, appropriate temperature, water), the spore germinates:

Germination Triggers: Germinants (amino acids, sugars, nucleosides) are recognized by germinant receptors (GerA, GerB, GerK proteins) in the inner membrane.

Molecular Events:

Germinant binding activates receptors

Water influx into spore core

SASP degradation exposes DNA

Metabolism reactivates

Cell wall remodeling

Emergence of vegetative cell

Timeline: Germination typically completes within 1-2 hours, returning the spore to exponential growth.

Developmental Gene Regulation: The Sigma Factor Hierarchy

The power of B. subtilis as a model organism becomes apparent in understanding how sporulation coordinates gene expression across thousands of genes over 8 hours. The elegant solution involves sigma factors—protein factors that direct the RNA polymerase to specific promoters.

The Sigma Factor Logic

During vegetative growth, one sigma factor (σA/SigA) predominates, directing transcription of vegetative genes. During sporulation, different sigma factors are activated sequentially in the two developing cells:

Temporal Hierarchy:

σH (SigH) - Early phase, both cells

Activates early sporulation genes

Activates genes for other sigma factors

Controlled by Spo0A~P

σF (SigF) - Forespore-specific, Stage II-III

Exclusively in forespore

Activates forespore maturation genes

Prevents inappropriate expression of forespore genes in mother cell

σE (SigE) - Mother cell-specific, Stage II-III

Exclusively in mother cell

Activates mother cell developmental functions

Prevents forespore-specific genes in mother cell

σG (SigG) - Late forespore, Stage IV-V

Activates late forespore genes

Germinant receptors; DNA protection proteins; SASP genes

σK (SigK) - Late mother cell, Stage IV

Mother cell-specific late functions

Lysis proteins; nutrient mobilization factors

Creating Cell Fate: How One Genome Makes Two Cell Types

The Fundamental Question: How does the same DNA sequence in forespore and mother cell produce different proteins?

The Answer: Different sigma factors activate different genes in each compartment.

Example: The gene spoIVB encodes a protein required for spore coat assembly. This gene contains:

A σE promoter (mother cell recognition sequence)

A σG promoter (forespore recognition sequence)

In the mother cell (Stage II-III), σE directs transcription of spoIVB mRNA. In the forespore (Stage IV-V), σG directs transcription of the same gene. The protein produced is identical; the timing and location differ based on which sigma factor is active.

Scaling this principle: Hundreds of genes are regulated by cell-specific sigma factors, producing distinct proteomes in forespore and mother cell despite identical genomic DNA.

Asymmetry Through Sigma Factor Localization

The most elegant aspect involves how cells localize sigma factors:

SigF Localization Mechanism:

pro-σF system: SigF is initially produced as an inactive precursor

Anti-sigma factors: Proteins like SpoIIAA, SpoIIAB prevent SigF activation

Forespore-specific phosphorylation: In the forespore, SpoIIAA phosphatase is activated (possibly by calcium influx or metabolic signals)

Result: Phosphorylated SpoIIAA cannot inhibit SigF; SigF activates → forespore genes express

In the mother cell:

Different signaling: SpoIIAB kinase remains highly active

SpoIIAA remains dephosphorylated: Continues to bind and inhibit SigF

Result: SigF remains inactive; forespore genes do NOT express

Research Insight: The pro-sigma/anti-sigma system exemplifies how cells can create distinct transcriptional programs in different compartments despite genomic identity. This principle—now recognized in eukaryotic development—was first clearly elucidated in B. subtilis.

Stress Response: The SigB General Stress Response System

While sporulation represents the "long game" of bacterial survival (create a dormant spore for long-term persistence), B. subtilis also possesses an immediate survival system: the general stress response (GSR) coordinated by the SigB transcription factor.

The SigB Regulon: >150 Genes of Rapid Response

When B. subtilis encounters stress—heat, osmotic shock, ethanol, UV light, nutrient starvation—SigB activates within minutes (5-15 minutes, compared to hours for sporulation). This master regulator controls over 150 genes, producing:

Stress Response Proteins:

Chaperones: GroES, GroEL, DnaK, DnaJ (help proteins fold correctly during stress)

Proteases: Clp family proteases (eliminate misfolded proteins)

DNA repair: Multiple DNA repair enzymes (counteract UV, oxidative damage)

Antioxidants: Enzymes destroying reactive oxygen species

Alternative metabolism: Enzymes for alternative carbon source utilization

Transporters: Nutrient uptake proteins for survival under starvation

Remarkable Feature: All these genes activate simultaneously in response to diverse stresses, providing comprehensive protection regardless of stress type.

The SigB Regulatory Mechanism: A Reversible Switch

SigB's elegance lies in its reversible activation—the cell can rapidly turn stress response on and off based on current conditions.

Activation Pathway:

Stress signal: Environmental stress (heat, osmotic shock, etc.)

Kinase activation: Stress activates specific kinase proteins

Anti-sigma phosphorylation: Kinases phosphorylate anti-sigma factors (RsbW, RsbX)

SigB release: Phosphorylated anti-sigma cannot bind SigB; it becomes free

RNAP binding: Free SigB binds RNA polymerase

Gene expression: SigB-RNAP complex recognizes SigB-dependent promoters

Stress genes activate: Protective genes express; proteins accumulate

Inactivation Pathway (when stress ends):

Phosphatase activation: RsbP phosphatase becomes active (in unstressed conditions)

Anti-sigma dephosphorylation: Phosphatase removes phosphate groups from anti-sigma factors

SigB re-sequestration: Dephosphorylated anti-sigma rebinds SigB

Gene silencing: SigB unavailable; no new mRNA synthesis

Stress response shutdown: Existing proteins degrade; cell returns to baseline

Advantage: This reversible mechanism prevents wasteful overproduction of stress proteins when conditions improve.

Stress-Sporulation Integration: Cellular Prioritization

A remarkable discovery revealed that stress response and sporulation are interconnected:

The Connection: SigB activates Spo0E, an aspartyl-phosphatase that dephosphorylates Spo0A~P.

The Logic:

When cells experience acute stress (heat, osmotic shock, etc.), SigB activates

SigB-driven Spo0E production dephosphorylates Spo0A~P

Spo0A~P inactivation blocks sporulation initiation

Cellular priority: "Handle immediate crisis (stress response) before committing to long-term dormancy (sporulation)"

Research Insight: Demonstrates how cells integrate multiple developmental programs, prioritizing based on current conditions. Under acute threat, focus on immediate survival; when stress ends, consider long-term strategies.

The Genome: Blueprint of a Workhorse Organism

Genomic Organization

The reference B. subtilis strain 168 possesses:

Genome size: 4,076,630 base pairs

GC content: 43.78% (relatively high; indicates metabolic complexity)

Total genes: ~4,200 protein-coding sequences

rRNA operons: 7 (unusually high; suggests importance of protein synthesis)

tRNA genes: 73

Metabolic completeness: 237 KEGG pathways mapped; 84 functional modules complete

Pathways Present:

Glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway

Citrate cycle (TCA)

Gluconeogenesis

Amino acid biosynthesis (all 20 standard amino acids)

Nucleotide biosynthesis

Vitamin/cofactor biosynthesis

Antibiotic synthesis (in some strains)

Biofilm formation

Spore formation

Implication: B. subtilis is metabolically versatile—capable of growth on diverse carbon sources, synthesizing all essential molecules de novo.

SubtiWiki: The Researcher's Goldmine

SubtiWiki (http://subtiwiki.uni-goettingen.de/) is arguably the most comprehensive bacterial genome database, containing:

4,200+ gene entries: Each with comprehensive annotation

Protein information: Sequences, properties, localization, structures

Protein interactions: Confirmed and predicted interactions

Regulatory elements: Promoters, sigma factor binding sites, regulatory proteins

Expression data: Transcriptomics from hundreds of conditions

Mutant fitness data: Which genes are essential; which are conditionally essential

Protein structures: Crystal structures where available; AlphaFold predictions

Complex structures: Protein-protein and protein-DNA complexes

Metabolic pathways: KEGG pathway integration

Homologs: Orthologs in other organisms

API access: Programmatic access for computational analyses

Research Application: Before conducting an experiment, researchers consult SubtiWiki to review existing knowledge, avoiding redundant experiments and building on established understanding.

The Understudied Proteins Initiative: The Research Frontier

Despite 180+ years of research and complete genome sequencing, approximately 25% of B. subtilis proteins remain functionally uncharacterized. The Understudied Proteins Initiative identifies 41 highly expressed but poorly studied proteins—likely important to the cell—as priorities for functional characterization.

Why This Matters: These proteins represent the genuine frontier of B. subtilis research. Understanding their functions will expand understanding of bacterial cell biology and potentially reveal entirely new cellular processes.

Research Approaches:

Global interaction studies (what proteins do they bind?)

Expression profiling (in which conditions are they expressed?)

Localization analysis (where in the cell are they located?)

Functional genomics (what happens when they're deleted?)

RNA-binding protein identification (do they interact with RNA?)

Recent Advances: Integration of Modern Biology

Metabolic Differentiation During Sporulation (2025)

A landmark study revealed that forespore and mother cell maintain independent metabolic programs during sporulation. Using sophisticated computational modeling combined with experimental manipulation:

SporeME2 model: Integrated metabolic-expression model of two-cell sporulation

Key finding: Mother cell and forespore have distinct enzyme expression; metabolic exchange occurs between compartments

Forespore dependency: Requires mother cell-derived biomass precursors and energy

Cell-specific essentiality: Some enzymes essential only in mother cell; others only in forespore for germination success

Implication: Sporulation represents true metabolic differentiation—not just gene expression changes but distinct metabolic reorganization.

Cryo-Electron Tomography of Sporulation

Direct visualization of sporulation at molecular resolution reveals:

Precise membrane architecture during engulfment

Chromosome organization changes

Protein complex assembly

Detailed 3D structure of developing spore

B. subtilis Beyond the Lab: Practical Applications

Industrial Biotechnology

B. subtilis is the industrial workhorse for:

Enzyme production: Proteases (detergent enzymes), amylases (starch degradation), lipases (biodiesel)

Protein secretion: Excellent secretion system produces heterologous proteins

Fine chemicals: Fermentation-based production of specialty compounds

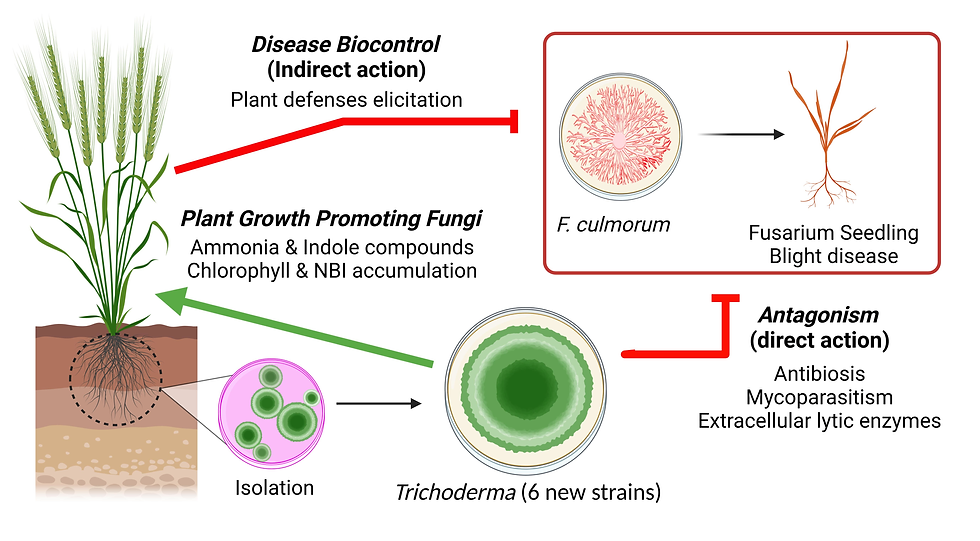

Agriculture & Soil Health

Plant growth promotion: Rhizosphere colonization; phytohormone production

Disease suppression: Antimicrobial compounds; ISR induction

Soil nutrient cycling: Enzyme production; phosphate solubilization

Medical Applications

Probiotic supplement: Spore stability allows oral delivery

Vaccine platform: Genetic manipulation enables antigen expression

Drug target: Understanding bacterial cell biology informs drug design

A Model for Understanding Life Itself

Bacillus subtilis has taught us fundamental principles applicable across all life:

How development works: Creating distinct cell types from identical DNA

How cells sense environments: Sophisticated environmental monitoring systems

How cells prioritize responses: Balancing competing developmental programs

How stress is managed: Rapid response coupled with long-term adaptation

How evolution innovates: Metabolic flexibility; stress response sophistication

For cellular biologists, Bacillus subtilis provides experimental advantages matched by no other organism: genetic tractability approaching E. coli, cellular complexity approaching eukaryotes, and a research legacy providing extensive foundation knowledge. As genomics, metabolomics, and systems biology deepen our understanding, B. subtilis remains the premier model for understanding how single cells organize themselves, respond to adversity, and adapt to changing environments.

The 25% of B. subtilis proteins with unknown function represent not finished research but an invitation—an invitation to discover principles of cellular organization, stress response, and development that B. subtilis, with its remarkable genetic toolkit and 8-hour developmental program, alone among model organisms can most elegantly reveal.

Scientific References

SubtiWiki Database Framework (2024) -

Microbe Profile: B. subtilis Model Organism (2020) -

https://www.microbiologyresearch.org/content/journal/micro/10.1099/mic.0.000922

B. subtilis as Model for Basic Cell Processes (2022) -

Exploring B. subtilis Ecology and Biotechnology (2024) -

Protein Aggregates Impact on Sporulation & Germination (2023) -

SubtiWiki Database Current State (2021) -

Understudied Proteins in B. subtilis (2023) -

B. thuringiensis Sporulation Mechanisms (Related) (2023) -

SirA Inhibits DnaA:DnaD During Sporulation (2022) -

Spore Formation Overview (2014) -

Milestones in B. subtilis Sporulation Research (2020) -

Extracellular Control of Sporulation (1988) -

Sporulation in Gut Isolate B. subtilis (2014) -

Unmasking Novel Sporulation Genes (2004) -

Sporulation Evolution & Specialization (2019) -

Recent Progress in Spore Germination (2025) -

Overview: Spore Formation Development (2002) -

Metabolic Differentiation During Sporulation (2025) -

General Stress Transcription Factor SigB (1997-1998) -

Genetic Diversity & Genomic Insights of B. subtilis (2025) -

B. subtilis Genome Sequence Blueprint (1999) -

Molecular Architecture of Sporulation (Villa Lab) -

Stress-Responsive Alternative Sigma Factor SigB (2020) -

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.01761/full

Complete Genome Analysis B. subtilis (2024) -

B. subtilis as Model Organism (2021) -

Global Analysis General Stress Response (2000-2001) -

B. subtilis Swiss Army Knife (2023) -

Transcriptional Profiling & Metal Ion Stress (2023) -

Complete Genome Sequence B. subtilis GL-4 (2025) -

SigB Activation Visible Light & Competence (2024) -

Slug: Bacillus-subtilis-model-organism-cellular-research

Related Internal Links:

Bacillus subtilis as a plant growth promoter

Understanding bacterial stress responses

Sporulation and spore formation mechanisms

Genetic tools for bacterial research

External Resources:

SubtiWiki Database:

PubMed B. subtilis research portal

NCBI Genome Database B. subtilis

IndoGulf BioAg B. subtilis Products:

https://www.indogulfbioag.com/microbial-species/bacillus-subtilis

Comments