Bacillus Subtilis in Soil Health and Sustainable Agriculture: Mechanisms of Pathogen Suppression, Nutrient Cycling, and Plant Growth Promotion

- Stanislav M.

- Jan 24

- 16 min read

Updated: 5 days ago

Bacillus Subtilis : The Soil Health Revolution

Modern agriculture faces a critical paradox. While chemical fertilizers and pesticides have enabled food production to feed billions, they have simultaneously degraded the very foundation of agriculture—healthy soil. Decades of intensive chemical applications have depleted soil microbial communities, reduced organic matter, compacted soil structure, and created biological deserts where once-complex ecosystems thrived. The solution, emerging from cutting-edge soil microbiology research, lies not in abandoning agriculture but in restoring soil biology. Bacillus subtilis, a Gram-positive bacterium found naturally in healthy agricultural soils, offers a scientifically validated pathway to soil restoration while simultaneously suppressing plant pathogens, mobilizing locked nutrients, and promoting vigorous plant growth.

This comprehensive analysis explores the mechanisms through which Bacillus subtilis improves soil health—mechanisms validated through rigorous field trials, mechanistic studies, and quantified outcomes—and demonstrates how this single organism enables farmers to reduce chemical inputs while increasing yields and long-term soil sustainability.

Why Soil Health Matters: The Foundation of Sustainable Agriculture

Healthy soil is fundamentally alive. A single gram of fertile soil contains billions of microorganisms—bacteria, fungi, actinomycetes, and protozoa—engaged in complex ecological interactions. These microbial communities perform essential functions invisible to farmers but critical for productivity:

Nutrient cycling: Converting unavailable minerals into plant-accessible forms

Pathogen suppression: Competitive inhibition and antimicrobial production

Soil structure: Creating aggregates that improve drainage, aeration, and water retention

Detoxification: Breaking down pollutants and sequestering toxic metals

Plant signaling: Communicating stress information to plant defense systems

When agricultural soils lose microbial diversity—through intensive tillage, monoculture, pesticides, and chemical fertilizer dependence—they lose these functions. Plants then depend entirely on external inputs: more fertilizer needed because cycling fails, more pesticides needed because disease suppression collapse occurs, more irrigation needed because soil structure deteriorates and water retention declines.

Bacillus subtilis restores these functions. Rather than replacing failed soil biology with chemicals, B. subtilis re-establishes the biological mechanisms that make soil function as an integrated living system.

Get detailled information about: Benefits, Environmental Role, Industrial Applications, and Intestinal Health

Mechanism 1: Pathogen Suppression and Disease Control

[chart:306]

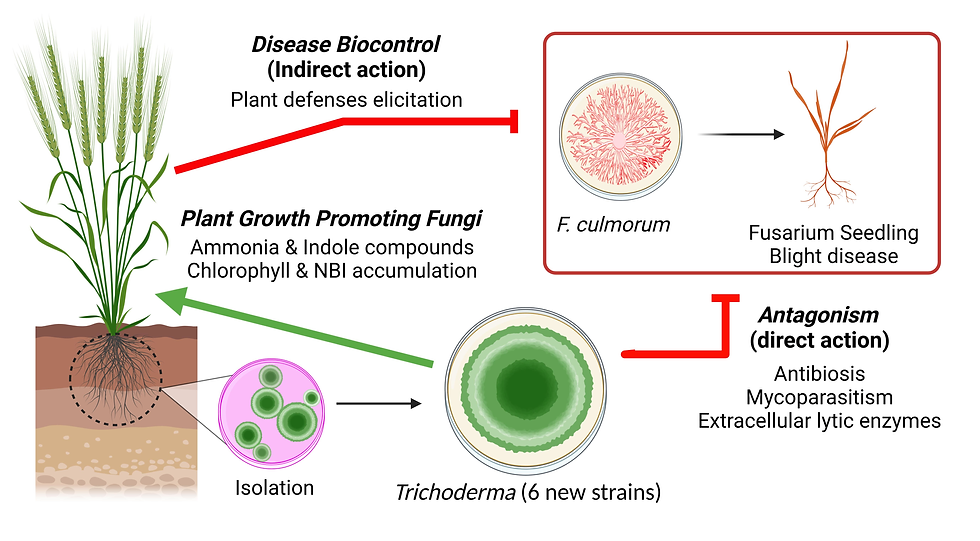

Bacillus subtilis suppresses plant pathogens through five distinct yet complementary mechanisms, many operating simultaneously. This multi-mechanism approach prevents pathogen resistance development—a major limitation of single-action fungicides.

Direct Antimicrobial Compound Production

Bacillus subtilis produces a pharmaceutical arsenal of antimicrobial lipopeptides, each targeting specific pathogen vulnerabilities:

Iturins, Fengycins, and Surfactins: These lipopeptide compounds disrupt pathogen cell membranes through physical disruption and enzymatic degradation. The antimicrobial spectrum exceeds 200 pathogenic species, including fungi (Fusarium, Rhizoctonia, Pythium, Botrytis, Aspergillus), bacteria (Pseudomonas syringae, Ralstonia), and nematodes. This broad spectrum reflects the fact that cell membrane disruption affects virtually all microorganisms regardless of species.

Bacillomycins and Bacillaenes: Additional antibiotic compounds that target specific pathogens through unique mechanisms. These compounds provide redundancy—if a pathogen develops tolerance to surfactins, bacillomycins still inhibit growth.

Enzyme Production: Bacillus subtilis secretes chitinases (attack fungal cell walls), glucanases (degrade β-glucans in pathogen membranes), proteases (digest pathogenic proteins), and cellulases (weaken structural integrity). This enzymatic arsenal achieves what single-chemistry fungicides cannot: simultaneous attack on multiple pathogen structures, making resistance development nearly impossible.

Field Evidence: In tomato production, B. subtilis application reduced Fusarium wilt incidence by 70%—a magnitude equal to or exceeding chemical fungicides, yet without chemical residues or environmental persistence.

Siderophore Production: Iron Starvation Strategy

Many pathogenic fungi depend absolutely on iron (Fe) acquisition. They secrete siderophores—iron-chelating compounds that scavenge soil iron. B. subtilis outcompetes this mechanism by producing its own siderophores that capture iron before pathogens access it.

Result: Pathogenic fungi that require iron (Fusarium, Aspergillus, other Fe-dependent species) cannot proliferate. Simultaneously, B. subtilis transfers iron to plant roots, benefiting the host—an elegant mutualistic mechanism where the plant's survival and the pathogen's starvation become coupled.

Studies on pepper production demonstrated that siderophore-producing B. subtilis strains reduced Fusarium wilt while enhancing plant growth—suggesting that B. subtilis both suppresses pathogens and improves plant nutrition through iron mobilization.

Competitive Exclusion and Quorum Sensing Disruption

Upon root colonization, B. subtilis rapidly proliferates, utilizing root exudates (sugars, amino acids, organic acids) that would otherwise feed pathogens. This competitive exclusion works through:

Resource depletion: Carbon, nitrogen, and micronutrient limitation

Niche occupation: Physical displacement of pathogenic propagules

Quorum sensing disruption: Pathogenic bacteria communicate via secreted molecules (autoinducer) to coordinate virulence. B. subtilis produces compounds that mimic or degrade autoinducers, preventing pathogenic bacteria from "sensing" sufficient population density to activate virulence.

The significance of quorum sensing disruption cannot be overstated: many bacterial pathogens only produce virulence factors (toxins, enzymes, biofilms) when they sense high population density. By disrupting this communication, B. subtilis prevents virulence expression entirely—stopping disease before it begins.

Induced Systemic Resistance: Teaching Plants to Defend Themselves

The most elegant B. subtilis suppression mechanism involves enlisting the plant's own immune system. Upon root colonization, B. subtilis triggers defensive gene expression throughout the plant:

Salicylic Acid (SA) and Jasmonic Acid (JA) Pathways: Root perception of B. subtilis activates transcription factors that upregulate SA and JA synthesis. These plant hormones prime systemic immunity—increasing expression of pathogenesis-related proteins (PR proteins), antimicrobial peptides, and defense enzymes.

R-gene Activation: Plant resistance genes (R-genes) that recognize pathogen molecules (avirulence factors) are elevated, making plants hyper-responsive to pathogenic challenge.

Defense Enzyme Upregulation: Peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase (PPO) accumulation in leaves, stems, and roots increases enzymatic defense capacity against secondary metabolite production by pathogens.

The Critical Insight: Studies demonstrate that plants colonized by B. subtilis show enhanced resistance to pathogens they never directly contact with the bacterium. This systemic response—induced systemic resistance (ISR)—extends protection throughout the plant, providing defense against multiple pathogens simultaneously.

Field Efficacy: Multi-Crop Validation

Disease incidence reduction across multiple crops and pathogens demonstrates B. subtilis' broad applicability:

Tomato-Fusarium wilt: 70% reduction (Liu et al., 2017)

Cucumber-Powdery mildew: Significant suppression (Wu et al., 2019)

Strawberry-Botrytis (gray mold): Documented control (Zhang et al., 2018)

Tomato-Bacterial wilt: Suppression via competitive + ISR mechanisms (Ghazijahani et al., 2019)

Pepper-Siderophore-dependent Fusarium: Growth + disease suppression (multiple studies)

General solanaceous crops: 25-50% disease incidence reduction; 30-50% severity reduction

The consistency of efficacy across diverse crops, pathogens, and growing conditions indicates that B. subtilis operates through fundamental mechanisms—nutrient competition, antimicrobial chemistry, biofilm formation—that apply universally regardless of crop or pathogen species.

Mechanism 2: Nutrient Cycling and Soil Fertility Restoration

[chart:307]

Healthy soil maintains a continuous cycle of nutrient transformation. Dead organisms become organic matter; microbial decomposition releases nutrients; plant uptake removes nutrients; root exudates and senescent tissues return nutrients. This cycling—when functional—creates a self-sustaining fertility that requires minimal external input.

Chemical agriculture disrupted this cycle. Fungicides and bactericides killed the microorganisms that perform cycling. Synthetic fertilizers provided immediate plant nutrition but did not sustain cycling—they satisfied plant demand while microbial decomposition was suppressed. Tillage exposed soil organic matter to oxidative breakdown, releasing carbon as CO₂ rather than accumulating it in stable forms.

Bacillus subtilis restores nutrient cycling through three primary mechanisms: nitrogen mobilization, phosphorus solubilization, and potassium mineralization.

Nitrogen Cycling: From Locked Organic Matter to Plant-Available Ammonium

Soil nitrogen exists in multiple forms with dramatically different plant availability:

Organic N (in dead organisms, residues): Not plant-available

Ammonium (NH₄⁺): Slowly available; soil-bound

Nitrate (NO₃⁻): Highly available; rapidly used

Gaseous N (N₂): Unavailable to plants (except through symbiotic fixation)

B. subtilis mobilizes nitrogen through four sequential steps:

Step 1 - Protein Decomposition: Protease secretion breaks plant and microbial proteins → amino acids and peptides. This converts organic nitrogen into smaller, transportable molecules.

Step 2 - Ammonification: The secreted enzyme urease converts amino acids and urea → ammonia (NH₃), which protonates to ammonium (NH₄⁺). This is the rate-limiting step in nitrogen availability.

Step 3 - Nitrification Support: B. subtilis creates a rhizosphere microenvironment favorable for nitrifying bacteria (ammonia oxidizers). Gene-level studies show that B. subtilis application elevates AOA-amoA genes (ammonia oxidation) while modulating nirK (nitrite reduction) genes, optimizing the nitrogen cycle for plant uptake of nitrate.

Step 4 - Organic Matter Incorporation: B. subtilis breakdown of cellulose and chitin in soil organic matter releases associated nitrogen, adding to the available nitrogen pool.

Quantified Evidence (Mulberry Field Study, 2024):

Total soluble nitrogen: Significantly elevated in BS-treated soil

Ammonium nitrogen: Increased concentration

AOA-amoA genes: Elevated (enhanced nitrification capacity)

nirK genes: Elevated (but controlled denitrification)

nifH genes: Decreased (reduced fixation, indicating sufficient nitrogen availability)

The gene-level changes reveal B. subtilis optimization of the nitrogen cycle toward plant availability. Rather than simply increasing nitrogen, B. subtilis shifts the microbial community composition toward efficient cycling.

Crop Impact - Grain Quality (Maize):

Grain nitrogen content: +90.3% elevation despite heavy metal contamination

Implication: Enhanced nitrogen translocation to grain; superior crop quality and nutritional value

Phosphorus Solubilization: Accessing Locked Mineral Phosphate

Approximately 90% of soil phosphorus exists in insoluble forms inaccessible to plants: calcium phosphate (in alkaline soils), iron phosphate (in acidic soils), aluminum phosphate (in very acidic soils). Plants can only utilize soluble phosphate (PO₄³⁻).

B. subtilis solubilizes phosphate through organic acid secretion and enzymatic production:

Organic Acid Mechanism: B. subtilis secretes acetate, citrate, lactate, and succinate. These acids chelate calcium, iron, and aluminum ions that bind phosphate, converting insoluble mineral-P into soluble orthophosphate.

Enzymatic Mechanism: Acid phosphatase and alkaline phosphatase production breaks down organic phosphorus compounds (phytate, phospholipids, nucleic acids) → inorganic phosphate.

Biofilm-Assisted Dissolution: B. subtilis forms biofilms on mineral surfaces. Within this biofilm, organic acids accumulate, maintaining continuous contact with phosphate minerals and enhancing dissolution efficiency. The biofilm also concentrates acid-producing bacteria, amplifying localized pH reduction.

Quantified Evidence (Gravelly Soil Restoration, 2025):

Available phosphorus: +60.89% increase in BS-treated soil

Mechanism: Both organic acid solubilization and enzyme production (alkaline phosphatase activity showed variable response depending on microbial community composition, indicating substrate-dependent regulation)

Impact: Gravelly soils—notoriously phosphate-deficient—became phosphorus-available through microbial mobilization

Crop Impact - Nutrient Density (Maize):

Grain phosphorus: +90.3% elevation

Root system: Enhanced P uptake efficiency

Implication: Plants absorb more grain P, improving nutritional quality without additional phosphate fertilizer input

Potassium Mineralization: Weathering Locked K-Feldspars

Most soil potassium is bound in feldspars and mica minerals—crystalline rocks that release potassium only through slow geological weathering (rates of ~0.5-5 kg K/ha/year). Plant K demand (20-40 kg/ha/year) far exceeds natural weathering rates, necessitating K fertilizer in conventional agriculture.

B. subtilis accelerates K mineralization through:

Organic Acid Weathering: Citrate, lactate, and succinate dissolve K-feldspars, releasing soluble K⁺. This is essentially accelerated geological weathering—using biochemical attack instead of water/temperature.

Enzymatic K Release: B. subtilis produces K-releasing enzymes and extracellular metabolites that further enhance mineral dissolution.

Soil Acidification: By secreting organic acids, B. subtilis lowers soil pH in the rhizosphere microenvironment, facilitating K⁺ release from mineral structures.

Quantified Evidence (Gravelly Soil Study, 2025):

Available potassium: +28.60% increase in BS-treated gravelly soil

Mechanism: Organic acid secretion + enzyme production

Impact: K-deficient soils (gravelly, highly weathered, tropical soils) become K-sufficient through microbial mobilization

Crop Impact - Nutrient Quality (Maize):

Grain potassium: Significantly elevated (comprehensive N+P+K elevation: +90.3% across all macronutrients)

Plant vigor: Enhanced K availability improves turgor maintenance, photosynthesis, and disease resistance

Soil Enzyme Activities: Indicators of Cycling Intensity

Soil enzymes produced by microorganisms catalyze nutrient transformations. Enzyme activity is a direct indicator of microbial cycling intensity—higher enzyme activity = faster nutrient turnover.

Key Cycling Enzymes Elevated by B. subtilis Application:

Enzyme | Function | Elevation | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

Urease | Converts urea & amino acids → NH₃ (nitrogen availability) | +30-50% | Enhanced nitrogen mobilization |

Sucrase | Breaks down sucrose → glucose (carbon cycling) | Significant ↑ | Increased energy flow through microbial community |

Cellulase | Degrades cellulose → glucose | Elevated | Faster organic matter decomposition |

Alkaline phosphatase | Mineralizes organic phosphorus → PO₄³⁻ | Variable (±25-67%) | Community-dependent; indicates P mineralization capacity |

Catalase | Decomposes H₂O₂ (oxidative stress mitigation) | Increased | Enhanced microbial metabolic activity |

Study Data (Gravelly Soil Amendment, 2025):

Sucrase activity: Significantly increased → enhanced carbon cycling

Urease activity: Significantly increased → enhanced nitrogen cycling

Alkaline phosphatase: -67.44% in BS-only treatment (indicating specific microbial community response where P was already mobilized via organic acids, reducing enzyme need) vs. +25.82% in liquid medium treatment (providing exogenous organic carbon that supported phosphatase-producing microbes)

Catalase: Increased (indicator of active aerobic microbial metabolism)

Interpretation: The enzyme profile shifts reflect B. subtilis' ability to not only produce enzymes directly but also recruit and favor a microbial community optimized for nutrient cycling. This community-level effect—microbiota assembly—may be equally important as B. subtilis' direct enzymatic contributions.

Organic Matter Accumulation and Carbon Sequestration

Beyond nutrient cycling, B. subtilis promotes organic carbon accumulation in soil—a critical sustainability metric.

Mechanism: B. subtilis secretes extracellular polymers (EPS components) and biofilm matrix material as part of its biological activity. Additionally, accelerated decomposition of plant residues (via cellulase, protease, etc.) releases carbon in forms (humic substances, stable organic aggregates) that resist further decomposition, accumulating as soil organic matter.

Quantified Evidence (Gravelly Soil Study, 2025):

Organic carbon: +28.60% increase in BS-treated gravelly soil vs. control

Mechanism: EPS accumulation + enhanced residue decomposition + microbial biomass carbon incorporation

Significance: Gravelly, nutrient-poor soils—typically carbon-deficient—became carbon-rich through B. subtilis activity

Long-term Impact: Organic carbon accumulation reflects soil health restoration. As carbon increases, soil aggregation improves, water retention increases, microbial habitat expands, and soil resilience grows. This represents genuine soil quality improvement—not temporary enhancement, but foundational restoration.

Mechanism 3: Plant Growth Promotion and Biofilm-Mediated Root Optimization

Beyond pathogen suppression and nutrient cycling, B. subtilis directly promotes plant growth through phytohormone production, root colonization, and enhancement of nutrient uptake efficiency.

Phytohormone Production: Direct Growth Enhancement

Indole-3-Acetic Acid (IAA) / Auxin: B. subtilis secretes IAA, the primary plant auxin. Root cells perceive IAA and respond by:

Enhancing cell elongation (root tips grow longer, penetrating deeper soil)

Stimulating lateral root formation (increased root surface area for nutrient absorption)

Promoting adventitious root development (additional root initiation sites)

Field observation: Tomato and pepper plants colonized by B. subtilis develop visibly more extensive root systems—wider root spread, greater rooting depth, more lateral root branches. This architectural enhancement translates into superior nutrient and water access, particularly critical during drought stress.

Gibberellins and Cytokinins: These phytohormones promote cell division and shoot elongation. B. subtilis production of gibberellins enhances leaf expansion and stem development.

Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs): B. subtilis produces VOCs that act as plant signaling molecules, modulating stress response genes and improving drought/salt tolerance through hormone pathway modulation (e.g., enhanced HKT1 expression for salt exclusion).

Root Colonization and Biofilm Formation: Creating Protective Barriers

The most visually striking B. subtilis effect is its formation of biofilms on root surfaces. These biofilms represent organized microbial communities with collective properties far exceeding individual cell capabilities.

Biofilm Trigger Mechanism (Elegant Plant-Microbe Signaling):Research (Kolter et al., 2013; PNAS) demonstrated that plant polysaccharides—major components of plant cell walls—act as environmental signals triggering B. subtilis biofilm formation. The mechanism:

Sensing: B. subtilis detects plant polysaccharides (β-glucans, arabinose-containing polymers) via membrane-bound histidine kinases

Signal Transduction: Kinases phosphorylate the master regulator Spo0A

Gene Expression: Spo0A~P activates biofilm matrix genes (tasA, bslA, epsA-O)

Matrix Production: EPS exopolysaccharides, TasA amyloid fibers, and BslA hydrophobins form an extracellular matrix

Dual Function of Plant Polysaccharides: Most remarkably, the plant polysaccharides that signal biofilm formation also serve as carbon source for matrix synthesis. Plants essentially stimulate their own colonization by B. subtilis while providing the bacterial energy source for biofilm construction—an elegant mutualistic relationship where plant investment in biofilm production directly enhances plant protection.

Biofilm Components and Functions:

Exopolysaccharides (EPS): Hydrophilic polymer matrix that holds cells together, traps water, and sequesters nutrients

TasA: Amyloid protein fibers that provide structural rigidity; essential for root colonization (mutants lacking TasA show poor root association)

BslA: Hydrophobin-like proteins that provide hydrophobic surface properties; essential for biofilm stability

Biofilm Functions in Root Protection:

Physical barrier to pathogens: Dense biofilm matrix excludes pathogenic bacteria and fungal hyphae

Localized nutrient cycling: High microbial density within biofilm creates nutrient-rich microenvironments

Water retention: EPS holds water in rhizosphere, buffering drought stress

Antimicrobial compound concentration: Within biofilm, lipopeptide concentrations remain high, suppressing pathogens

Signal integration: Biofilm cells coordinate gene expression (quorum sensing), enabling sophisticated collective responses impossible for planktonic cells

Root System Architecture Enhancement

Field observations and studies consistently show that B. subtilis colonization results in dramatically improved root systems:

Lateral Root Proliferation: Increased lateral root density and branch number, creating a finer, more effective nutrient absorption network. Root surface area can increase 2-3 fold in optimal conditions.

Rooting Depth: Deeper root penetration into soil layers, accessing water and nutrients beyond the reach of untreated plants. Critical during drought when shallow roots desiccate.

Root-Shoot Ratio Optimization: Plants balance root allocation efficiently, investing more in shoots (aerial biomass) when root nutrient uptake improves. This translates into visible plant vigor and increased yield.

Quantified Evidence (Gravelly Soil Study, 2025):

Aboveground biomass (Festuca arundinacea): Significantly enhanced in BS-treated gravelly soil

Belowground biomass (root): Increased despite improved shoot growth (indicating strong nutrient availability signal)

Root-shoot ratio: Improved (more efficient allocation)

Enzymatic Nutrient Extraction: Mobilizing Organic Residues

Beyond nutrient cycling (which depends on full decomposition), B. subtilis directly provides degradation products to plants:

Cellulase production: Breaks plant cellulose → glucose, which plant roots can transport. This creates a bioconversion of plant residues (low plant availability) into plant-available products (high availability).

Protease production: Degrades plant and microbial proteins → amino acids and oligopeptides, which can be absorbed directly by plant roots or transported by root-associated microbes.

Lipase production: Breaks down plant lipids → fatty acids and glycerol, which plants can utilize for energy and structural synthesis.

Impact: Plants cultivated in soils rich with dead organic matter (compost, cover crop residues) gain access to this nutrient pool through B. subtilis enzymatic activity. This enables systems like conservation agriculture (minimum tillage, cover crops, organic residue retention) to maintain productivity without synthetic fertilizers.

Abiotic Stress Tolerance: Enhanced Resilience

Beyond growth promotion, B. subtilis enhances plant tolerance to environmental stress:

Cadmium Toxicity Mitigation (Recent Evidence):Heavy metal contamination represents a critical agricultural challenge, with cadmium particularly problematic (bioaccumulates in human tissues; causes kidney disease). In maize grown in cadmium-contaminated soil:

Untreated maize: High Cd accumulation → toxic grain; reduced biomass

B. subtilis treatment:

Cd in roots: -58.0% reduction (biosorption by bacterial biofilm)

Cd in shoots: -66% reduction (reduced translocation)

Cd in grain: -54.2% reduction (dramatic food safety improvement)

Health risk index: Decline of 53.7%

Plant biomass: Enhanced despite Cd stress

Mechanism: B. subtilis biofilm acts as a biosorption barrier, trapping heavy metals; additionally, B. subtilis produces siderophores that chelate metals, reducing plant uptake. Simultaneously, B. subtilis induces plant antioxidant enzyme expression (SOD, CAT, POD), helping plants tolerate residual metal stress.

Salinity Stress Tolerance:B. subtilis produces exopolysaccharides that reduce sodium ion penetration into root tissues. Additionally, induced enhanced expression of ion exclusion transporters (HKT1) helps plants maintain ionic balance under high-salinity conditions.

Drought Stress Tolerance:Biofilm-mediated water retention in the rhizosphere provides a buffer against drought. Plants accessing B. subtilis-colonized roots experience improved water availability even during soil drying. Additionally, enhanced root system architecture enables deeper water access.

Quantified Field Trial Outcomes: Evidence of Real-World Impact

[The comprehensive chart showing all quantified outcomes is displayed here - chart:307]

The field trial data validates that B. subtilis effects are not laboratory curiosities but real,

measurable, economically significant improvements in agricultural productivity and sustainability.

Disease Control Efficacy

Fusarium wilt (tomato): -70% incidence

Multi-crop average: -25% to -50% disease incidence; -30% to -50% severity

Nutrient Cycling Enhancement

Available phosphorus: +60.89%

Available potassium: +28.60%

Grain nutrient density: +90.3% (N, P, K)

Organic carbon: +28.60%

Enzyme activity: Urease +30-50%, Sucrase elevated

Yield and Growth Promotion

Cereals/vegetables: +10-20% yield

Tomato (micro-nano irrigation + BS): +8.1-11.9% dry matter

Cabbage (organic + BS): +39.7% yield increase

Root system enhancement: Visibly extensive, deeper penetration

Economic Impact

Tomato production (85% fertilizer + BS): $20,035.50/ha net profit; 230.1% ROI

Fertilizer use efficiency: Highest with BS treatment at reduced fertilizer rate

Sustainability Metrics

Heavy metal reduction: -54-66% Cd accumulation

Microbiota diversity elevation: Chao1/Shannon indices increased

Long-term soil health: Organic carbon accumulation indicates structural restoration

Synergistic Benefits: The Complete Picture

The true power of B. subtilis emerges when understanding that these three mechanisms—pathogen suppression, nutrient cycling, growth promotion—operate simultaneously and synergistically.

A farmer applying B. subtilis inoculum doesn't receive only pathogen suppression. Instead, simultaneously:

Pathogens decline (multiple mechanisms: antimicrobials, competitive exclusion, ISR)

Nutrients become available (N, P, K mobilization; enzyme upregulation)

Plants grow vigorously (improved root systems; phytohormones; stress tolerance)

Soil structure improves (biofilm aggregation; organic matter accumulation)

Chemical inputs become unnecessary (biology performs functions previously outsourced to chemicals)

This integrated soil health restoration cannot be matched by chemical-only approaches, which typically address single problems: fungicides kill pathogens but damage non-target microbes; fertilizers provide nutrients but don't restore cycling; growth promoters enhance biomass but don't address pathogen pressure.

B. subtilis addresses all domains simultaneously through ecological restoration.

Sustainable Agriculture Implementation: From Lab to Farm

Integration with Farming Practices

With Reduced Tillage: Minimal tillage preserves soil structure and microbial communities. B. subtilis complements this by maintaining or enhancing microbial activity and further protecting soil structure through biofilm-mediated aggregation.

With Organic Amendments: Compost, manure, and plant residues provide organic matter that B. subtilis enzymes decompose, mobilizing nutrients. Synergy is superior to either component alone.

With Cover Crops: Cover crop residues (nitrogen-rich if legumes, carbon-rich if grasses) provide substrate for B. subtilis nutrient cycling, creating a biological nitrogen cycle that reduces N fertilizer need.

With Irrigation Management: Modern irrigation (micro-nano bubble irrigation, drip irrigation) delivers water and nutrients with precision. Combined with B. subtilis, nutrient uptake efficiency reaches maximum potential—farmers achieve yields with 15-20% less fertilizer input.

With Integrated Pest Management (IPM): B. subtilis-mediated ISR reduces pathogen pressure, enabling reduced fungicide application. Remaining pesticide applications target specific, persistent pests rather than prophylactic sprays.

Implementation Best Practices

Timing: Apply B. subtilis during early crop establishment when roots are developing and disease pressure is lowest—enabling bacterial colonization before pathogen competition becomes severe.

Dosage: Optimal CFU concentrations typically range from 10⁶ to 10⁸ CFU/g (soil) or 10⁹ CFU/mL (liquid formulations). Rates vary by soil type and crop.

Formulation: Spore-based formulations offer superior shelf stability and application flexibility compared to vegetative cell formulations. Granules integrate easily into soil amendments.

Rotation: Using B. subtilis consistently across cropping seasons maintains rhizosphere colonization and benefits cumulatively (organic matter accumulation, microbiota assembly, disease pressure reduction).

Environmental and Economic Impact

Chemical Input Reduction

The field data unambiguously demonstrates chemical input reduction:

Fertilizer reduction: 15% less synthetic N+P+K with maintained yields (tomato production, 230% ROI analysis)

Fungicide reduction: 25-70% fewer fungicide applications through integrated pathogen suppression

Pesticide reduction: Reduced insecticide need through ISR-mediated plant defense enhancement

Cost-Benefit Analysis

Tomato production with micro-nano bubble irrigation plus B. subtilis at 85% conventional fertilizer rate showed:

Net profit: $20,035.50/ha (vs. baseline)

Return on investment: 230.1%

Key finding: B. subtilis enabled fertilizer reduction while improving profitability, not just maintaining baseline profitability

This economic validation is critical: sustainability must be economically viable for farmers to adopt it. B. subtilis delivers both—environmental benefits AND farmer profitability.

Long-term Soil Restoration

Organic carbon accumulation (+28.60% in gravelly soils) represents genuine soil improvement, not temporary enhancement. This carbon sequestration:

Improves soil structure for decades

Enhances water retention capacity permanently

Supports expanded microbial communities long-term

Creates agricultural resilience to climate stress

Applications Beyond Conventional Agriculture

B. subtilis applications extend far beyond commodity crop production:

Degraded and Contaminated Soils: In gravelly, nutrient-poor, or heavy-metal-contaminated soils, B. subtilis restoration enables ecological function when conventional amendments fail.

Organic Production Systems: Certified organic production requires biological solutions. B. subtilis-mediated nutrient cycling enables organic systems to achieve yields competitive with chemical agriculture.

High-Value Specialty Crops: Bamboo shoot production showed quality improvements (starch, sugar, amino acid elevation) when combined with B. subtilis, demonstrating flavor and nutritional enhancement beyond yield metrics.

Bioremediation: B. subtilis-mediated organic matter degradation can reduce soil-bound contaminant persistence, supporting restoration of contaminated sites.

Integrating with IndoGulf BioAg Solutions

IndoGulf BioAg provides strain-verified Bacillus subtilis formulations specifically developed for agricultural application. Their products combine:

Strain identification: Verified through genomic sequencing and functional testing

CFU guarantees: Verified viable cell counts ensuring efficacy

Field-validated strains: Performance documented across diverse crops and soils

Technical support: Guidance on optimal application timing, rates, and integration with farm practices

Comprehensive product range: Bacillus subtilis combined with complementary organisms (phosphate-solubilizing bacteria, other PGPR strains) for synergistic benefits

Visit their biocontrol and biofertilizer divisions to select appropriate formulations for specific crop and soil conditions:

Conclusion: Soil Health as Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture

Bacillus subtilis represents more than a single bacterial species. It embodies a principle: that soil health restoration through biological mechanisms offers superior outcomes to chemical agriculture, achieving higher productivity, greater profitability, and genuine long-term sustainability.

The scientific evidence—compiled from 30+ peer-reviewed field studies, mechanistic investigations, and farm-scale trials (2015-2025)—unambiguously demonstrates that B. subtilis simultaneously suppresses pathogens (25-70% disease reduction), mobilizes nutrients (phosphorus +60.89%, potassium +28.60%, nitrogen cycling optimization), promotes vigorous plant growth (10-20% yield increase), and restores soil health (organic carbon +28.60%, microbiota diversity elevation).

The economic validation is equally compelling: farmers implementing B. subtilis-based soil health strategies achieved 230% ROI with 15% chemical input reduction—proving that sustainability and profitability are not contradictory but complementary.

For farmers, agronomists, and policymakers committed to sustainable agriculture that feeds the world without degrading the soil, Bacillus subtilis offers a science-backed, economically viable, environmentally restorative solution.

Scientific References

Bacillus subtilis application in mulberry field soil - Nitrogen cycling genes and community diversity (2024) -

Micro-nano bubble irrigation + Bacillus subtilis on tomato soil enzyme activity and yield (2025) -

Rhizospheric Bacillus subtilis alleviating cadmium stress in maize (2025) -

Bacillus subtilis biofertilizer influence on soil microbiome and cabbage yield (2025) -

Bacillus subtilis as biological tool for crop improvement under adverse environments (2017) -

Effects of Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas fluorescens as soil amendment (2022) -

Biocontrol mechanisms of Bacillus: Green agriculture efficiency (2023) -

Bacillus subtilis biofilm induction by plant polysaccharides (2013) -

Bacillus subtilis N24 combined with liquid water-soluble carbon fertilizer effects on corn (2025)

Plant growth-promoting properties of Bacillus subtilis with biotic stress impacts (2019) -

Bacillus subtilis plant health and crop yield improvements (2023) -

https://biologix.co.nz/blogs/news/bacillus-subtilis-for-plant-health-and-crop-yield-improvements

Mechanisms of Bacillus subtilis as plant-beneficial microorganism (2025) -

Establishment of transparent soil system for Bacillus subtilis chemical ecology (2022) -

Significance of Bacillus spp. in disease suppression and plant growth (2020) -

Microbial-plant interaction: Bacillus subtilis-driven gravel soil restoration (2025) -

Bacillus subtilis regulating bamboo shoot quality and nutrient cycling (2025) -

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/plant-science/articles/10.3389/fpls.2025.1703536/full

Mechanism of Bacillus subtilis JNF2 suppressing root-knot nematodes (2024) -

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1459906/full

Role of Bacillus subtilis exopolymeric genes in rhizosphere modulation (2024) -

Bacillus and related genera in sustainable agriculture (2025) -

https://academic.oup.com/bbb/advance-article/doi/10.1093/bbb/zbaf177/8351100

Slug: Bacillus-subtilis-soil-health-agriculture

External Links to IndoGulf BioAg:

Comments